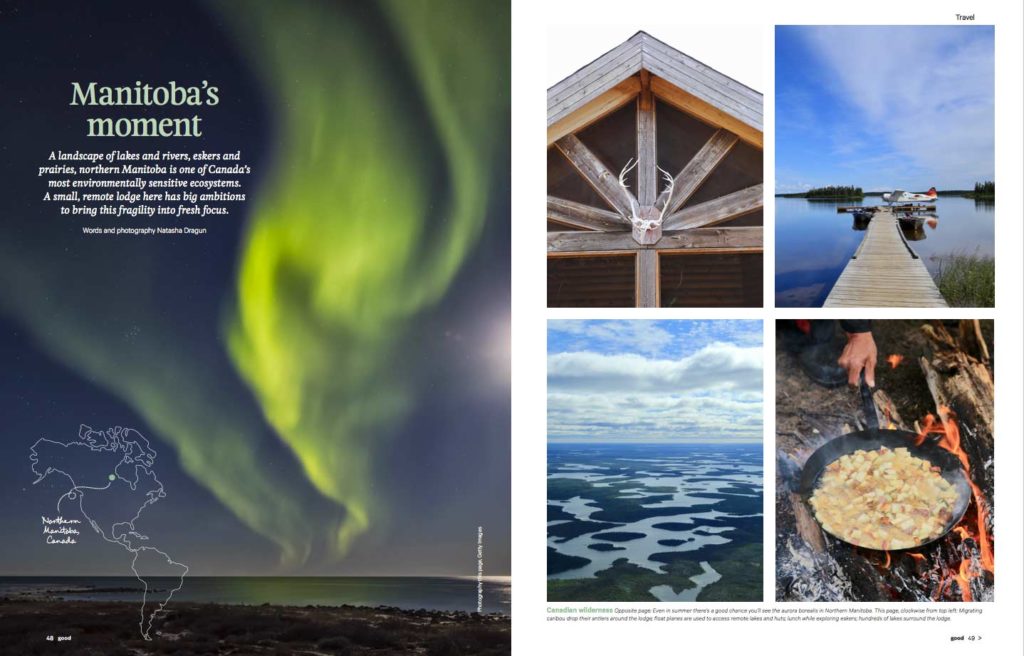

A landscape of lakes and rivers, eskers and prairies, northern Manitoba is one of Canada’s most environmentally sensitive ecosystems. A small, remote lodge here has big ambitions to bring this fragility into fresh focus.

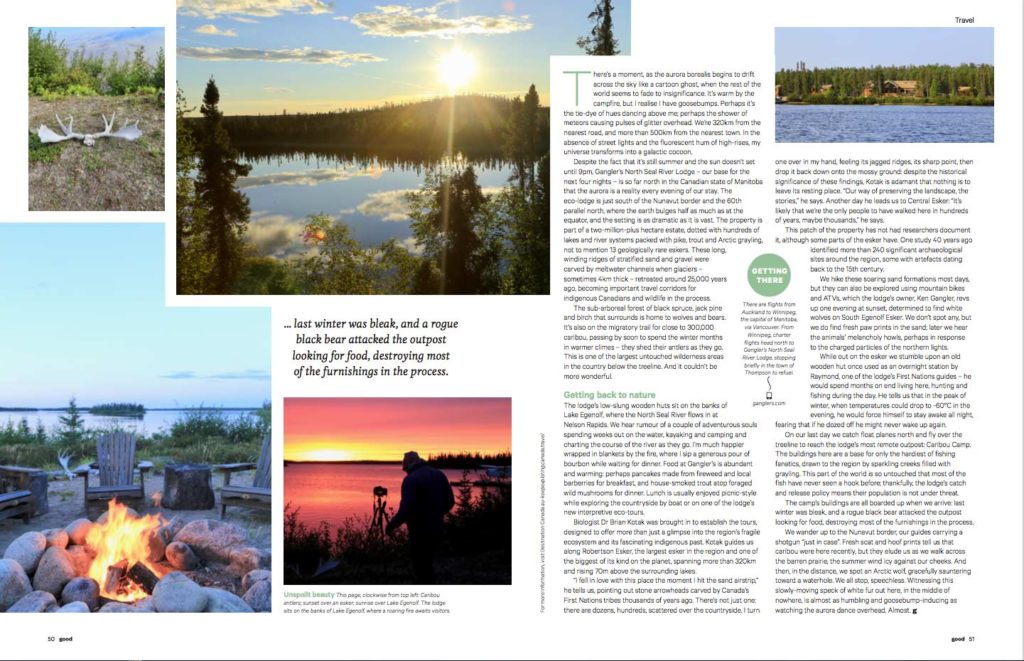

There’s a moment, as the aurora borealis begins to drift across the sky like a cartoon ghost, when the rest of the world seems to fade to insignificance. It’s warm by the campfire, but I realise I have goosebumps. Perhaps it’s the tie-dye of hues dancing above me; perhaps the shower of meteors causing pulses of glitter overhead. We’re 320km from the nearest road, and more than 500km from the nearest town. In the absence of street lights and the fluorescent hum of high-rises, my universe transforms into a galactic cocoon.

Despite the fact that it’s still summer and the sun doesn’t set until 9pm, Gangler’s North Seal River Lodge – our base for the next four nights – is so far north in the Canadian state of Manitoba that the aurora is a reality every evening of our stay. The eco-lodge is just south of the Nunavut border and the 60th parallel north, where the earth bulges half as much as at the equator, and the setting is as dramatic as it is vast. The property is part of a two-million-plus hectare estate, dotted with hundreds of lakes and river systems packed with pike, trout and Arctic grayling, not to mention 13 geologically rare eskers. These long, winding ridges of stratified sand and gravel were carved by meltwater channels when glaciers – sometimes 4km thick – retreated around 25,000 years ago, becoming important travel corridors for indigenous Canadians and wildlife in the process.

The sub-arboreal forest of black spruce, jack pine and birch that surrounds is home to wolves and bears. It’s also on the migratory trail for close to 300,000 caribou, passing by soon to spend the winter months in warmer climes – they shed their antlers as they go. This is one of the largest untouched wilderness areas in the country below the treeline. And it couldn’t be more wonderful.

Getting back to nature

The lodge’s low-slung wooden huts sit on the banks of Lake Egenolf, where the North Seal River flows in at Nelson Rapids. We hear rumour of a couple of adventurous souls spending weeks out on the water, kayaking and camping and charting the course of the river as they go. I’m much happier wrapped in blankets by the fire, where I sip a generous pour of bourbon while waiting for dinner. Food at Gangler’s is abundant and warming: perhaps pancakes made from fireweed and local barberries for breakfast, and house-smoked trout atop foraged wild mushrooms for dinner. Lunch is usually enjoyed picnic-style while exploring the countryside by boat or on one of the lodge’s new interpretive eco-tours.

Biologist Dr Brian Kotak was brought in to establish the tours, designed to offer more than just a glimpse into the region’s fragile ecosystem and its fascinating indigenous past. Kotak guides us along Robertson Esker, the largest esker in the region and one of the biggest of its kind on the planet, spanning more than 320km and rising 70m above the surrounding lakes.

“I fell in love with this place the moment I hit the sand airstrip,” he tells us, pointing out stone arrowheads carved by Canada’s First Nations tribes thousands of years ago. There’s not just one: there are dozens, hundreds, scattered over the countryside. I turn one over in my hand, feeling its jagged ridges, its sharp point, then drop it back down onto the mossy ground: despite the historical significance of these findings, Kotak is adamant that nothing is to leave its resting place. “Our way of preserving the landscape, the stories,” he says. Another day he leads us to Central Esker: “It’s likely that we’re the only people to have walked here in hundreds of years, maybe thousands,” he says.

This patch of the property has not had researchers document it, although some parts of the esker have. One study 40 years ago identified more than 240 significant archaeological sites around the region, some with artefacts dating back to the 15th century.

We hike these soaring sand formations most days, but they can also be explored using mountain bikes and ATVs, which the lodge’s owner, Ken Gangler, revs up one evening at sunset, determined to find white wolves on South Egenolf Esker. We don’t spot any, but we do find fresh paw prints in the sand; later we hear the animals’ melancholy howls, perhaps in response

to the charged particles of the northern lights.

While out on the esker we stumble upon an old wooden hut once used as an overnight station by Raymond, one of the lodge’s First Nations guides – he would spend months on end living here, hunting and fishing during the day. He tells us that in the peak of winter, when temperatures could drop to -60°C in the evening, he would force himself to stay awake all night, fearing that if he dozed off he might never wake up again.

On our last day we catch float planes north and fly over the treeline to reach the lodge’s most remote outpost: Caribou Camp. The buildings here are a base for only the hardiest of fishing fanatics, drawn to the region by sparkling creeks filled with grayling. This part of the world is so untouched that most of the fish have never seen a hook before; thankfully, the lodge’s catch and release policy means their population is not under threat.

The camp’s buildings are all boarded up when we arrive: last winter was bleak, and a rogue black bear attacked the outpost looking for food, destroying most of the furnishings in the process.

We wander up to the Nunavut border, our guides carrying a shotgun “just in case”. Fresh scat and hoof prints tell us that caribou were here recently, but they elude us as we walk across the barren prairie, the summer wind icy against our cheeks. And then, in the distance, we spot an Arctic wolf, gracefully sauntering toward a waterhole. We all stop, speechless. Witnessing this slowly-moving speck of white fur out here, in the middle of nowhere, is almost as humbling and goosebump-inducing as watching the aurora dance overhead. Almost.